PROGRAM

REVEAL Indigenous Art Awards (2017)

As part of its plans to increase support for Indigenous art practices, The Hnatyshyn Foundation launched the REVEAL Indigenous Art Awards to honour Indigenous Canadian artists working in all artistic disciplines. The comprehensive one-time program of awards and promotional activities, including 150 cash awards of $10,000 each awarded in 2017, have fueled the creation of new artistic works and left a lasting cultural legacy.

The Awards were intended to recognize emerging and established Indigenous artists working in traditional or contemporary practices. The awards were given in six artistic categories: dance, music, theatre, literature, film/video (media arts), and visual arts/fine craft.

A special event honouring the artists was held in Winnipeg on May 22nd, 2017.

-

Ann McCain Evans • The Hnatyshyn Foundation • The Assembly of First Nations • Shirley Greenberg • Gerda Hnatyshyn • Sheila Bayne • The Canada Council for the Arts • The Catholic Archdiocese of Ottawa • The Government of Saskatchewan • William & Shirley Loewen • Dasha Shenkman • The Stonecroft Foundation • James and Louise Temerty • Anonymous • Shelley Ambrose & Doug Knight • The Asper Foundation • Bax Investments • Ann Birks • The Bragg Foundation • Bruce Power • The John and Bonnie Buhler Foundation • Astrid Cohen • John Craig • The Danbe Foundation • The Government of the Northwest Territories • Gowling WLG • Greystone Managed Investments • Eric Jackman • Vera Klein • The Koerner Foundation • Yann Martel • Ann McCaig • Hon. Margaret McCain • Joanne and Rob Nelson • Nuclear Waste Management • James & Sandra Pitblado • The University of Saskatchewan • Todd Burke & Jennifer Block • BLP Investments Limited • Bruce & Vicki Heyman • Provincial Investments Inc. • Rob Guenette • Roman Catholic Toronto Diocese • Anglican Church of Canada • Gerry Arial • The Canadian Electrical Association • Sandra Irving • Harbour Grace Shrimp Co. Ltd • Myles Kirvan • Labrador Sea • Arnie Thorsteinson and Susan Glass • CanadaHelps • Barbara Fischer • Victoria Henry • John Hnatyshyn • Beverley McLachlin • Michael Moldaver • Maurice Panchyshyn • Rev. Gerard Pettipas • Ewa Piorko • Joanna Piorko • Nicole Presentey • Christopher Speyer • Dr. Shailendra Verma

Gifts in kind

Air Canada • Beaver Bus Lines Ltd • Fairmont Hotel Winnipeg • Office of the Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba • VIA Rail

-

Victoria Henry (Chair)

Chair of The Hnatyshyn FoundationBarry Ace

Visual artistDenise Bolduc

Creative producer, programmer and arts consultantChristine Lalonde

Curator and art historianDaniel David Moses

Poet, playwright, author and teacherFlorent Vollant

Composer, performer

-

The Honorary Patrons of this project embodied the values and aspirations of the community they represent and joined in supporting this unique initiative.

James Bartleman

Photo : Philippe Landreville

A member of the Chippewas of Rama First Nation and best-selling author of As Long as the Rivers Flow and The Redemption of Oscar Wolf, James Bartleman grew up in the Muskoka town of Port Carling. Following a distinguished 35-year career in the Canadian Foreign Service, he served as Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario from 2002 to 2007. A key initiative during his tenure was the creation of the Lieutenant-Governor’s Book Program, which saw more than a million used books collected and donated to First Nations schools. In 2008, the Ontario Government established the James Bartleman Aboriginal Youth Creative Writing Award to recognize Aboriginal youth for their creative writing talent.

Rosalie Favell

Rosalie Favell is an award-winning photo-based artist, born in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Drawing inspiration from her family history and Métis (Cree/English) heritage, she uses a variety of sources, from family albums to popular culture, to present a complex self-portrait of her experiences as a contemporary aboriginal woman. Her work has appeared in exhibitions in Canada, the US, the United Kingdom, France, and Taiwan and has been acquired by the National Gallery of Canada, the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, and the Rockwell Museum of Western Art, among others. She has worked with grassroots organizations in Winnipeg, with Inuit educational groups in Ottawa, and with Nepalese women’s groups in Kathmandu.

James Hart

Photo : Ramsay Pictures

James Hart is one of the Northwest Coast’s most renowned artists. In addition to his mastery in carving monumental sculptures and totem poles, he is a skilled jeweller and printer and is considered a pioneer in the use of bronze among the Northwest Coast Artists. He is represented in major collections around the world including in the National Gallery of Canada, the Canadian Museum of History, and the Smithsonian Museum, and has had numerous solo exhibitions. Commissioned for the new Michael Audain Museum in Whistler, The Dance Screen is James Hart’s most ambitious project to date. As Chief of the Sangaahl Stastas Eagle Clan since 1999, he holds the name and hereditary title of his great-great-grandfather, Charles Edenshaw.

Waubgeshig Rice

Photo : Shilo Adamson

An author and journalist from Wasauksing First Nation, Waubgeshig Rice developed a strong passion for storytelling as a child while learning about being Anishinaabe. The stories his elders shared and his unique experiences growing up in his community inspired him to write creatively. Stories he wrote as a teenager were published as Midnight Sweatlodgein 2011. His debut novel, Legacy, was published in 2014. He graduated from Ryerson University’s journalism program in 2002, and has worked in a variety of media across Canada. Along with reporting the news, he has produced television and radio documentaries and features, and currently works as a video journalist for CBC News Ottawa. In 2014, he received the Anishinabek Nation’s Debwewin Citation for Excellence in First Nation Storytelling.

Please note that the REVEAL Honorary Patrons do not play an operational role with the Foundation and were not involved in the review or selection of candidates for the awards.

-

The program was closed as of June 1st, 2016.

Overview

These awards were intended to recognize emerging and established Indigenous artists working in traditional or contemporary practices. They were given in six artistic categories including dance, music, theatre, literature, film/video (media arts), and visual arts/fine craft.

Artists selected to receive an award were entitled to use the proceeds of the award at their own discretion.

Eligibility

To be eligible to apply, artists were required to:

Be of Indigenous descent.

For the purposes of these awards, Indigenous people include First Nations, Inuit and Métis people of Canada.Be a Canadian citizen or permanent resident of Canada.

Be at least 18 years of age at the time of application.

Define and describe theirself as a practicing artist.

Artistic Disciplines

Dance, Music, Theatre

For applicants in dance, music and theatre, the awards were intended for performance. Oral traditions, storytelling, spoken word, pow wow and hip hop were included in these categories. Choreographers, arrangers, composers and directors were not eligible.

Literature

The awards in literature were intended for writers in fiction, non-fiction and poetry, as well as playwrights.

Film/Video (Media Arts)

The awards in film and video were intended for creators working in film and video (analog or digital), including animation, who retain creative control of their work. Producers and screenwriters were not eligible.

Visual Art & Fine Craft

The awards in visual art and fine craft included conventional visual art practices (painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, printmaking, mixed media). Installation, performance art and conceptual art were also eligible.

In fine craft, contemporary and traditional practices were eligible, including, carving, jewellery making, ceramics, glass work, bead work, fiber, textile and fashion, and include other traditional/culture-based materials such as fish scale, caribou hair tufting, and quillwork.

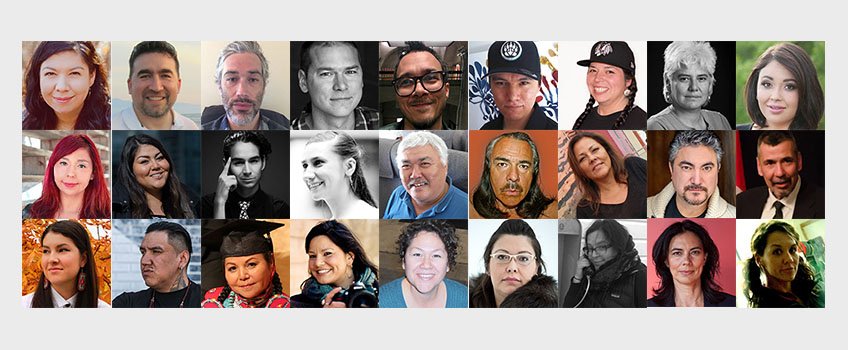

Laureates

-

Nathan Adler is an emerging writer and storyteller from Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation, Ontario.

“I am a storyteller regardless of which medium I’m working in: a painting, an audio track, a video, or the craft of writing. Stories that always seek to entertain, enlighten, and de-colonize.

Drawing heavily on my family history, Anishinaabek language, culture, and methods of storytelling, as well as historical research, dreams, intuition, and synchronism, I write mostly fiction in the Urban Fantasy and Horror genres, the sort of writing I most like to read, and I strive to write as well as my favourite authors, who tend to have a literary, gothic aesthetic, and a dark sense of humour. Stories are the best, funnest, most awesome thing to be involved in creating, and I can’t think of anything better than to be a good storyteller.”

-

Susan Aglukark is an Inuit singer from Arviat, Nunavut.

“As much as I love singing (and I love singing), and song writing, I love more the work of awakening and healing our inner selves through art and music. The process behind each album represents the places or points I am at in my personal healing journey.

My vision is to spread the power of music as a healer.”

-

Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm is a writer from Chippewas of Nawash First Nation, Saugeen Ojibway Nation (SON).

“My work is part of a continuum of artistic cultural practice including oratory, story cycles, songs, chants, invocations, poetry, libretto, stories, novels, essays, radio plays, creative non fiction, ‘experimental’ writing and multidisciplinary works. It arises from the traditions of my people, and the canon of Anishinaabek orature/literature. SON is the home territory of generations of renowned writers, orators, and storytellers including Nahnebahwequay, Basil Johnston, Duke Redbird, Lenore Keeshig and my grandmother Irene Akiwenzie.

My work is inspired by my mixed ancestry and the work of other Indigenous artists. In dispelling stereotypes and telling the truth of Indigenous realities in my own way according to concepts of truth and beauty rooted in Indigeneity and Anishinaabe culture, my work is firmly decolonial, a practice of cultural resurgence, affirmation and survivance. It rejects marginalization, centring itself within Anishinaabek creative cultural practice. My writing is inherently political, a form of activism, empowerment and resistance as well as a creative and spiritual act. Stories in my newest book, The Stone Collection, examine love and the ways in which our perceptions of people and the world around us can be misleading and incomplete. In the Anishnaabek language stones are ‘alive,’ infused with life force. Although many of the stories are about loss, under the surface they are ‘alive,’ celebrating the beauty and preciousness of life and the web of connections that join and strengthen us.”

-

Donald Amero is a singer-songwriter from Manitoba. His first four albums generated nine national and international awards, as well as a Juno nomination in 2013.

“I want to feel good about what I’m doing. With over nine years as a full time musician, I’ve come to understand that music is a business and there are certain freedoms that commercially successful artists have to give up. I don’t want to give up anything. I want to write songs that will have a positive impact on our young people. I want to work with musicians who are also great people. I want to perform in places where I’m needed. I want to have conversations with people from every walk of life. I want to sing from my heart. I want to make the world a better place. I also want to win a JUNO. ;)”

-

Judy Anderson is a mixed media artist and artisan working in Regina. She is of Cree descent from the George Gordon First Nations, Saskatchewan.

“Much of my work examines First Nation’s issues through the lens of traditional and contemporary forms of art making. My work is deeply personal with a focus on spirituality, family, and graffiti with the purpose of honoring people in my life. I have worked with hand made paper creating traditional parfleche bags, miniature burial mounds casted from my pregnant body, and a big drum. Recently I have made hand made paper clothing based upon the Spirit names of friends and families. At the same time, I have researched and learned traditional art making using traditional materials creating primarily beaded pieces. With this knowledge I fuse traditional and contemporary art forms. One such piece honours my graffiti artist son, Cruz. I have recreated Cruz’s first graffiti burner in beads on moose hide. Exploit Robe (Toying Around), the first piece in this series of four, acknowledges his inexperience as a writer while honouring the beginning of his journey as an artist. My most recent works honour Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women where I provide space for the exploration into experiences, sensibilities, thoughts, fears, and hopes presented as female-based realities. These works include sound, beading, handmade-paper, and found objects that reveal the complexities of personal relationships. These works open the dialogue around the importance of honouring people and the many ways these ceremonies can enrich the lives of both First Nation and non-First Nations people.”

-

Joanne Arnott is a Métis writer and performer from Manitoba.

“Musicality is a primary quality of my work - the murmuring of a talking circle and the wind in the grass - whether in poetry or prose. I engage in both big picture and political matters as well as the most intimate human moments, with a personal voice that seeks to share life at the deepest levels. Topics may arise from within, be suggested by a conversation, or come at the request of an editor: whatever the motivation, I pour my best self into each glass.”

-

Cherrish Alexander is a carver from Kitwanga, B.C.

“I started my training in 2007 at Freda Diesing School of Art in Terrace BC. I was the first woman in the very first year of the program. My Instructors were Stan Bevan, Ken Mcneil and Dempsy Bob. My artwork is my life's passion; I enjoy bringing the art back to my community of Gitwangak.”

-

Joe Jaw Ashoona is an Inuk carver from Cape Dorset based in Montreal.

“I sold my first carving at the age of seven. My mother and grandfather taught me how to work with a variety of stone, petrified whalebone, mammoth ivory, musk ox horn and antler. I draw my inspiration for subject material from the time I spent growing up on the land. My memories of the Nunavummiut animals inform my carvings. A variety of which can be seen on my website.

I dedicate much of my time to making sizeable carvings ranging from 50-150 pounds each. This is my full-time occupation and one piece can take weeks if not months to complete.

Carving is the way that I perserve Inuit stories and traditional knowledge of the land, sea and animals. It is also a conduit for me to help other carvers grow their potential and become more valued by the industry for their work.

At Ashoona Arts 360, I am trying to bring awareness of the realities of the Inuit art world and how reconciliation is also needed in this domain. Through events like my most recent exhibition 20 Claws and 4 Fangs, I brought in throat singers, shared a qulliq ceremony, country food, Inuit tools and fashion and displayed my carvings to a diverse group in Montreal. I want to bring Inuit carving further by fulfilling a social mandate of public education and to work closely with other Inuit artists to achieve this.

We have many social issues to overcome in the North, but I believe that education in and the proliferation of Inuit art will help us tackle them. I will continue to carve as long as my body will allow and to devote my life’s work to the advancement of Inuit art on an international scale.”

-

Eugene Alfred is a Tutchone/Tlingit carver and painter from central Yukon.

“For me, art is always opening an opportunity to go through new experiences and to let more stories to be heard. I have been inspired by my uncles, Roger and Jerry Alfred, who in turn, learned our stories from my grandfather and other elders in our community. Increasingly, I am taking that direction with my pieces, finding my own unique experiences in my homeland.

For the past 30 years, I have been painting and carving northwest coast art. My first teacher was Dempsey Bob (Taltan/Tlingit Artist) in 1986 and I later worked with Ken Mowatt (Gitxsan Artist) for 4 years between 1991-1995. Doing native art has been a dream come true and an important way to express myself. After all these years doing northwest coast art, I am finally finding a style that I can call my own.

Receiving a REVEAL Indigenous Art Award will give me the opportunity to carve and bring back ‘dance sticks’ for our dance group Selkirk Spirit Dancers and our community of Pelly Crossing. These dance sticks were once used in our community feasts and potlatches about 80 years ago. They were taken from original home of Fort Selkirk and put into museums around the world. They were taken from our community when people were out on the land. These dance sticks are an important missing link to our past and the future of our young people. These dance sticks will be hand carved with homemade tools and use yellow cedar wood.”

-

Morgan Asoyuf is a jeweller of the Eagle Crest, Tsm'syen Nation, Lax Kwallams band, from Port Simpson, B.C.

“I create one of a kind jewelry that is completely handmade from start to finish. I use the German technique of hollow building to produce layers and shadow. Starting with flat sheet the metal is shaped and soldered. I am both a purist and an experimenter. I handmake all my tools, melt and pour metal, make my wire and sheet. I use experimental textures and construction to see how far I can bend the ideas of form. I am involved in every process of creating a piece, doing my own gem setting and stone cutting. I don't care about the time I care about the quality. About doing justice to the art form.

Always a book lover, I studied many different eras and became obsessed with Art Nouveau (Mucha and Lalique), Egyptian goldsmithing, and Hellenistic art.

Beyond my personal interest of historical art and the processes that create it, I care deeply about the forwarding of traditional Tsm’syen art and culture.

Each piece tells a story. Designs depict animal crests that tell the stories of familial rank and migratory paths over many generations. Using hand engraving for the traditional Tsm’syen forms, I then use color and textures to show different aspects of this visual storytelling.

Northwest coast art is transformative. Creating it allows me to speak in silence and feel connection to my ancestors. This is why teaching the next generations is such a huge part of my life, because this art form brings healing.”

-

Tara Beagan is a writer and storyteller of the Coldwater Band, Ntlaka'pamux Nation from Lower Nicola Valley, B.C.

“I strive to share the stories I am entrusted with, to candidly pose questions and provoke thought, thereby lessening the gaps of misunderstanding and disinterest that divide the multitude of communities in Canada and the world.”

-

Lori Blondeau is a Cree/Saulteaux/Métis artist. She holds an MFA from the University of Saskatchewan, and has sat on the Advisory Panel for Visual Arts for the Canada Council for the Arts and is a co-founder and the current director of TRIBE, a Canadian Aboriginal arts organization. Her practice includes both visual and performance contemporary art.

“My work explores the influence of popular media and culture (contemporary and historical) on Indigenous self-identity, self-image, and self-definition. I am currently exploring the impact of colonization on traditional and contemporary roles and lifestyles of Indigenous women. I deconstruct the images of the Indian Princess and the Squaw and reconstruct an image of absurdity and insert these hybrids into the mainstream. Humor is essential to my work. The performance personas I have created refer to the damage of colonialism and to the ironic pleasures of displacement and resistance.

The images of the Indian Princess and Squaw have had a significant impact on societies’ perception of Indigenous women and serve as inspirations for most of my work. Surprisingly, we still see popularized images of the Indian Princess being created by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. You can find these products being sold in Indian Museums and souvenir shops across North America. These are testament to the general public’s idealized perception of beautiful Indigenous women as being exotic and hard to find; virtually non-existent.”

-

Sonny Assu is a We Wai Kai visual artist working in Campbell River, B.C.

“Shedding light on the dark, hidden history that Canada continues to harbour towards its Indigenous people is a main driving force behind my work. I often use humour as a way to ease the viewer in or out of the conversations I create, and the use of autobiographical components is my way of placing a human face on the contemporary and historical realities of being an Indigenous person in Canada. Within this, I deal with the loss of language, loss of cultural resources, and the effects of colonization upon the Indigenous people of North America.

I use painting, sculpture, large scale installations, print, and photography as a way to challenge our Western civilization’s consumption culture through introspection of our consumer driven monolithic ways.

By melding Kwakwa_ka_’wakwak art, cultural and societal structures with various Western art movements, I am challenging and persisting that consumerism, branding, and technology are new modes of totemic representation.”

-

Christi Belcourt is a visual artist, Michif (Metis Nation), from Manitou Sakahigan (Lac Ste. Anne), Alberta.

“My love for this world, and my love for everyone and everything is what drives me. My paintings are a reflection of all that is right in the world, they are for me an antidote for what I see around me that troubles me. Art is one of the most powerful tools there is to try to create a better world.”

-

Kristen Auger is a fine craft artist from Bigstone Cree Nation living in Fort St. John, B.C.

“My work speaks about my experience as a nêhiyaw (Plains Cree) woman. It is an expression of the natural world and represents my cultural traditions. I strive to communicate Indigenous world views in a contemporary manner. My aim is to breathe life into the continuance of traditional Indigenous arts. I research each piece with the guidance of knowledge keepers. The designs I choose represent my culture, family and personal life. My hope is that my work will cultivate a greater awareness in society with respect to Indigenous cultures in Canada.

For my latest piece Nîpihikân Pimâtisiwin: Flower Life, I was inspired by the Cree Hoods that were first recorded in 1670 and worn by my ancestors. Generally, married women would wear them in hunting rituals or other ceremonies. Nîpihikân Pimâtisiwin: Flower Life represents my life journey. The designs emblematize periods of cultural growth. One of the flowers depicted in the piece is the wild rose as it symbolizes my cultural nation in Alberta. I created this piece during the course of my first pregnancy. I've explored the traditional roles of mothers and wives from an Indigenous perspective. This work embodies Indigenous womanhood and connection to mother nature. Furthermore, it highlights cultural continuance and the transfer of Indigenous knowledge from one generation to the next.”

-

Michael Belmore is a visual artist from Lac Seul First Nation living in Ottawa.

Born and raised in Northern Ontario, he has been a full time practicing artist since graduating from Ontario College of Art and Design in 1994. Belmore’s employment of a variety of materials and processes may at times seem disjointed, yet, the reality is that together his work and processes speak about the environment, about land, about water, and what it is to be Anishinaabe. Much of his practice has been exhibition-based but more recently he has been participating in artist residencies where he creates site-specific works that respond to the local environment.

Seemingly small things, simple things, inspire his work; the swing of a hammer, the warmth of a fire, the persistence of waves on a shore. Through the insinuation of these actions, a much larger consequence is inferred. Materials have a voice, they speak a language, and they speak to each other. Through his work Belmore attempts to join in that conversation, offering a voice that speaks about the past and the future, about our connection to this island and to its ever-changing landscape.

-

Kenny Alvin Baird is a Métis Cree visual artist from the Michelle Callihou Band, Alberta working in Toronto.

“Upon receipt of funding I will continue pursuing my current investigations with assemblage painting. After several decades of working in various mediums from installation, sculpture, film, and mixed media. I’ve come full circle, returning to my original medium of choice: painting. I believe everything is cyclical, eventually returning to its origins.

Although I have not abandoned my practice in these other areas I’ve chosen this time to focus on discovering a new creative direction by utilizing an old practice. A course reflecting present experiences without repeating any ground I’ve already explored.

I’m experimenting with the use of distressed mirror and glass over painting on hardwood with the use of animal totem iconography, like black ravens and albino wolves. The use of reflective surfacing, exampled in the work “Satellite” appeals to my interest to merge the viewer’s image, reflected in the distressed mirror with the painted image of the animal. It is a metaphor of shape shifting the human spirit with the animal spirit, incorporating both into the work as one.

This imagery, nature in beauty and decay continues to be my primary source of inspiration. It is the constant which also accompanies my attraction with polarities. I am of mixed blood heritage, Metis Plains Cree. Painting is a therapeutic emotional exercise, for me to study and reclaim aspects of my native ancestry, identity, including concepts of boundaries, both real and imagined.”

-

Jordan Bennett is a Mi’kmaq visual artist from Ktaqamkuk, Newfoundland.

“Through the processes of sculpture, painting, digital media, installation, sound installation and other mediums my work explores observations and influences from historical and popular culture, new media, traditional craft and cultural practice to convey connection to land; the act of visiting, and my familial histories. My current body of work utilizes painting, carving, projection, photography and sound to challenge perceptions of indigenous histories, stereotypes and presence with a particular focus on exploring Mi’kmaq and Beothuk visual culture of Ktaqamkuk, Newfoundland.”

-

Shuvinai Ashoona is an Inuit visual artist from Cape Dorset, Nunavut.

Ashoona began drawing in 1996. She works with pen and ink, coloured pencils and oil sticks and her sensibility for the landscape around the community of Cape Dorset is particularly impressive. Her recent work is very personal and often meticulously detailed. Shuvinai’s work was first included in the 1997 Cape Dorset annual print collection with two small dry-point etchings entitled Interior (97-33) and Settlement (97-34). Since then, she has become a committed and prolific graphic artist, working daily in the Kinngait Studios.

"When I start to draw I remember things that I have experienced or seen. Although I do not attempt to recreate these images exactly, that is what might happen. Sometimes they come out more realistically but sometimes they turn out completely different. That is what happens when I draw."

-

Mary Anne Barkhouse is a sculptor and jeweller from the Nimpkish Band, Kwakiutl First Nation, from Alert Bay, B.C., currently living in Ontario.

“I explore environmental concerns and indigenous culture through my mixed-media sculpture installations. I feel that it is critical for personal and cultural analysis on our relationship to land and how it can be improved for the future, from a political and environmental point of view.

My sculptural practice draws upon moments in colonial, contemporary and natural history to reflect on issues of sovereignty and survival. I use materials, such as bronze, porcelain, and velvet, for their associations with value, strength and authority. An example of this would be installations from the Boreal Baroque exhibition, which situate Canadian wildlife amongst furnishings inspired by designs typically produced in 18th century Paris.”

-

Jaime Black is a Metis visual artist working in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

“My work is situated in an understanding of the body and the land as sources of historical and cultural knowledge and is centered around themes of memory, identity, place and resistance. I am interested in the body/land as sites of social and political struggle, sites of memory and as vulnerable and often contested spaces. I am interested in the ways in which we can re-establish agency and resilience through interactions between the land and the body.

My most recent photo based work, Conversations with the Land, explores the relationship between the land and the body. This project involves direct interactions between the body/subject and the landscape, drawing on the traditional land based practice of Indigenous cultures. Performative acts, encounters and elements of installation combine to create images that engage with notions of Indigenous identity, evoking cultural memory by asserting cultural ties to the land. This work also seeks to ground and identify women as the central support of strong social structures (matriarchal gathering/hunting cultures) and posits a present and future where women embody this position.”

-

Nicole Camphaug is a fine craft artist from Rankin Inlet, currently working in Iqaluit.

“I have been sewing for a great number of years but have only recently been doing the sealskin shoes. I love working with sealskin and was always looking at ways to use it in a manner that promotes it and not just in the colder months. I found that people would look forward to the colder months in order wear their sealskin products. Inuit and non-Inuit who love to promote their support for the arctic and culture, seem to jump at the opportunity to wear their products. I came up with the wonderful idea of how to use sealskin anytime, anywhere.

I absolutely adore sealskin and it is very important to my Inuit culture to use it, since we eat the seal for nutrition, the fur is a byproduct, rather than the sole purpose. Inuit hunt seal to feed our families, our communities and being able to use the fur is amazing. Inuit make mitts, hats, coats, kamiit (winter, waterproof fur boots), purses, hunting bags, you name it, we will make it. I like the idea of modern shoes being adorned with sealskin, it’s another use for our furs.

As I do not make the actual shoe itself, I do like using an already made shoe, that way I am not limited to one style or size or colour. I have creative freedom to use a shoe that inspires me or challenges me. I also like that people can provide me with their favorite shoe to have them renewed, if you will. There really is no limit on what I can do with adorning sealskin to footwear.”

-

David Charette is a singer from the Ojibwe Nation, Wikwemikong unceded Indian territory, Ontario.

“My stage name is ‘White Deer.’ As I am loon clan, the creator gave me this voice to heal our nation. Loons are known for their voices. I don't just want to change the way society looks at our people but I want to heal those that need it at the time.”

-

Sid Bobb is a Sto:lo/Salish actor and writer from Seabird Island First Nation.

Combining his cultural knowledge, experience as an arts organization leader, educator and theatre artist, Sid Bobb has been committed to helping bring Indigenous stories and culture to the forefront. He is inspired by the transformative power of the rich artistic and cultural history of his Sto:lo / Métis ancestry and related communities. Sid's artistic practice is at the core of his individual, familial and nation's identity, continuity and forward vision.

Sid is the son of Lee Maracle of Tsleil Waututh First Nation and Raymond Bobb of Seabird Island First Nation. His family is rooted in a multi arts and intergenerational cultural practice. This artistic practice and knowledge transference happened in both a rural and urban context. Sid’s early experience was within a multi-generational context, with an awareness and commitment to countering the historic and continuing negative impacts of colonialism.

Over the past 15 years, Sid's artistic focus and efforts have been on strengthening the platform for children, youth and women. Historically, a Salish man's role is to uphold and support the women in their family and community. With the intergenerational impact of the continuing colonialism, breaking the veils of gender inequality and marginalization of children has been a major focus of Sid and Aanmitaagzi's efforts. This is noted in the women's focus in the narrative of their many community-engaged arts projects and the artistic roles created for, women, children and youth. For nine years he has also been host of CBC televisions award winning program, Kid's Canada. Performing for and with children is also a mutually necessary and enriching experience.

-

Celeigh Cardinal is a Métis musician from the Peace Region, working in Morinville, Alberta.

“I began singing at three months old. As I repeated a melody over and over, my mother was elated. At the age of four I sang on stage for the first time. When I was 12, I joined a choir on weekends, played piano, and started writing songs. When I was 19 I joined my first band and began performing professionally. When I was 22 I discovered I was about to embark on the greatest and scariest path I’ll ever know, single motherhood.

Though becoming a mother was time consuming and set me back as far as my personal career goals of pursing music, I quickly found that my need for more income, and the birth of my greatest muse, allowed me to get back on track. When I was 25, my son was almost three, I began playing again. I am lucky to have known my calling and to have dreams and passions from such a young age. It is a little unlucky, that it is an art form, and arts are very hard to make a living from. So, I have learned many ways to turn music and singing into a day job/night job, that allows me to support myself and my child. I have become a promoter, an open stage host, a music teacher, a social media expert, a booking agent, a pub singer, a merchandise salesman, a grant writer, and tour manager. These are all skills I have picked up in my 17 years of professional playing.

All I ever wanted was to make music the way I earn my living. I now have bigger career goals that include recording, touring, and more sustainability. Maybe even one day, medical benefits. I know I've taught my son the importance of following/living your dreams, and I am living mine the best I can.”

-

Christa Couture is a Cree and Métis musician from the Prairies living in Toronto.

“Everyone is looking to feel less lonely. The focus of my work comes down to the conversation that happens between performer and listener. In that exchange, I feel both sides are asking the question ‘Do you know what I mean?’ searching for and finding common ground and connection between open ears and hearts.

My work draws on loss, grief, illness, longing, survival, and resilience through writerly, at times even playful, skill with words. Through songs, I share what comes next after loss, what comes after you pick up the pieces, and how to find hope in the shadows of our harder, complex human experiences.

My practice is contemporary music that at its core is Indigenous culture: conversational, autobiographical work drawn from my personal experiences; experiences that reflect my intersecting identities as a Cree woman and woman with a disability (or halfbreed and cyborg as I choose to identify), as well as a mother and artist. Until the studio recording process, nothing is written down: my work is created, learned, and shared as a practice of aural/oral tradition.”

-

Ludovic Boney is a Huron/Wendat visual artist working in Lévis, Quebec.

Boney's minimalist formal research integrates the constraints of the material into the concept of his works. His sculptures take on the appearance of aesthetic structures, with planes and solids giving way to lines and voids to signify the creation of new spaces: intimate and discreet. In this way, the interiority of the sculpture becomes increasingly important, to the point of sometimes confusing the essence of the work and its influence on its surroundings.

Since it's the atmosphere of a place that inspires him, his sculptures are always imbued with it, integrating harmoniously with idiosyncratic aesthetic references. Industrial mechanics, and the noise they produce, are elements he incorporates into his research, development of form, choice of material and elaboration of concept.

From these juxtapositions emerges a powerful, vibratory effect of unity. The forms he creates are voluminous, and their robustness is invariably contrasted by a disturbing impression of precarious balance that prompts the viewer to question or contemplate.

Boney is deeply attracted to public art, that is, "art that is accessible to the users of our parks, streets and cities". Most of his creations are designed to be understood by the lay public as well as by art insiders (craftsmen, visual artists, engineers and architects).

-

Cliff Cardinal is an actor, writer and singer from Pine Ridge working in Toronto.

“I’m an Urban First Nation’s person. I’m constantly an outsider. This perspective has shaped the stories I tell and write and songs that I sing. I grew up in urban centers feeling Indian and loving Indian, but not having a constant connection with others who share spiritual practices. Most of my work is not culturally specific. The cultural references are general to being ‘Indian,’ as opposed to a specific First Nation. My work is usually set in Toronto or some generalized city, town, or reserve. I find myself fascinated by stories and songs about marginalized people.

Poetics is a life-long endeavour. Each project has been challenging, heartbreaking, and elating; and has given me the opportunity to challenge myself to take on a new aspect of poetry. I write about what scares and embarrasses me. I explore pain and what I’m ashamed of; and I go there with love.

Things are bad; but everything’s going to turn out alright after all. I’m haunted by how much of our culture and how many of our stories and people were stolen. My poetry attempts to create meaning and beauty from heartbreak and loss. Stylistically, I steal from different mediums and moments in my life to create new myths. The time we spend together in our brief walk on earth is sacred, and worth telling stories and singing songs about.”

-

Francine Cunningham is a Cree author from Saddle Lake, Alberta.

“I entered storytelling through theatre and from there fell in love with shaping experiences for an audience and the power that speaking truth can have. I studied creative writing and theatre throughout my BFA at The University of British Columbia. During my MFA at UBC, I pushed myself to learn as much as possible about the writing craft from many writers. While studying I wrote a young adult novel which features a young Cree Métis girl named Sage who struggles with mental illness and follows her journey to healing after an attempted suicide. The project that I am currently working on it titled The way I was brought into the world was this and is a non-fiction memoir that looks at trauma and how it affects a person’s genetic tags and influences mental illness by exploring the research surrounding epi-genetics. Specially, it is exploring the intergeneration effects of the systemic policies of abuse, assimilation and attempted genocide against the First Nation’s people of Canada. By exploring these effects in one family, my memoir hopes to add to the ongoing conversation surrounding reconciliation. I am striving to bring my own experiences with being a Cree Métis woman who grew up in an urban environment to the conversation surrounding Indigenous issues. I would like to see in literature more stories that reflect the growing urban Indigenous population and our unique lens. I’ve worked with urban Indigenous youth for ten years and know they’re looking for characters that reflect their lives.”

-

Rita Bouvier is a Métis writer from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

“I love writing! In my writing, I strive to balance ‘a good story’ with sound and images drawing on both my first and second language. I often play with the meaning and musicality of both languages as a way of connecting with others and to the Great Mystery. I love the power of leaving a still-life image on paper with my choice of words and space as silences. Likewise, I balance personal experience, response and observation with imagination to transcend the material and imaginative failures of our time. I do so by remembering knowledge passed down to me, by dreaming, by gathering strength and reconciling what has happened and is happening in our communities and to the natural environment, and by rejoicing in the life around me. I often find myself returning to place and to the sounding – the music of our mother's movement and voice.

My writing reflects everyday life in the communities I am a part of, because it is sacred. I strive to find the spiritual core of life and living; although, I am sometimes filled with an immense sense of loss, shame and longing. Of course, I have also found beauty and joy. Through my writing, professional and creative, I try to tell a larger story, one that is filled with love for family, community and this place I know. Like my ancestors, all I can be is in awe of her power. Humbled.”

-

Liz Carter is a mixed media artist from Alert Bay.

Not being able to settle on one medium, Carter creates work using an array of mixed media. Her journey through the labyrinth of mixed meanings embedded within her Native ancestry and her blue-collared upbringing is driven by process. She uses culturally significant materials like wood, copper, buttons, and animal skins in new ways- with hints from the past and questions about how cultures are interpreted.

Carter’s displacement from her cultural roots has had a profound effect on her work as an artist. She explains, "it’s a life riddle" that has taken her upon a biographical journey full of unanswered questions about displacement and loss of tradition. Carter's search has uncovered a realm of commercial images of the 'Imaginary Indian' that profoundly impacts our perception. It has also revealed the determined struggle of Kwakwaka'wakw culture to carry forward ancient symbols and meanings into a contemporary life.

-

Raes Calvert is a Métis actor, producer, and director based in B.C.

“I first began performing on stage while I was attending high school in Richmond. I was drawn to theatre performance because it allowed me the opportunity to be present and live in the moment (something that is sorely missing in the day to day lives of those living in the ‘Western World’). At the age of seventeen, I decided I would pursue acting, but more specifically performance in theatre, as my life's work. I attended Studio 58 at Langara College where I received my Diploma in Performing Arts. During my time at Studio 58, I realized what an amazing platform live performance is. Theatre has the power to incite critical thinking, create public discourse, and affect social change, (not to mention, it's also a lot of fun!).

In January of 2010 I co-founded a theatre company, and began creating and producing my own work. Through my experiences as a theatre creator I began to shape myself as an artist and decipher what live story-telling means to me. Creating a company has given me the chance to work, not only as a performer, but also as a designer, a director, a writer, and as a producer and theatre administrator. Being an indigenous story-teller has given me the incredible opportunity to connect to my aboriginal heritage, network with other First Nations artists, and use my art form as a means of cultural exchange.”

-

Christian Chapman is an Anishinabe visual artist from Fort William First Nation.

“I make art because it’s my way of paying respect to the past by way of telling a visual story. Storytelling is very important to me. Stories of heritage, identity and personal experience are explored in my art. The oral tradition of storytelling is important to the preservation of the evolving Anishinabe culture.

I like to think my art helps keep stories alive for future generations to come. I remember the stories my grandmother would tell. She would tell stories deeply rooted in family history and background. Whether it’s a story from my grandmother or from my father, stories come from all over my community and beyond. I use these narratives to create my images. I hold the highest regard for storytellers. A good storyteller can evoke tears and laughter.”

-

Beatrice Deer is an Inuit/Mohawk musician from Quaqtaq, Nunavik.

“Music is something I consider a part of me. I use it to express myself, express my love for my culture, my personal experiences and messages that I feel would help someone in some ways. I like to contribute to Inuktitut music. I like to incorporate traditional Inuit throat singing to my contemporary music, as we are an adaptable people to modern times. Music can touch people no matter what language we speak. It speaks for those who can’t speak for themselves. I love to show my culture through my performances by singing in my language and wearing traditional/contemporary clothing I have created, or wear Inuit made accessories on stage. I like to show the rest of the world that we are just as talented as the rest. I also focus on being an example to youth about living a healthy, sober lifestyle.”

-

Wally Dion is visual artist from Yellow Quill First Nation, Saskatchewan.

“A large part of my studio practice has included the use of recycled computer circuit boards. Instantly recognizable around the world, circuit boards are the hieroglyphics of our time. For many people, computer circuitry is as enigmatic as the symbols carved into the side of a 3000 year-old temple and yet we have enormous faith in their ability to furnish us with our lifestyles.”

-

Tara Gereaux is a Métis writer from southern Saskatchewan.

“My earliest childhood memories are of my mother teaching me to read, and of trying to write my own stories – and all of this before I started school.

Writing is how I fit into the world. It’s who I am. I didn’t learn of my Métis history, however, until I was an adult, after I began publishing and producing my work. Though my first book was published after I began exploring my Métis culture and identity, it had been written and accepted for publication before I started reconnecting with my heritage.

Now, my writing and stories explore this discovery, and the choices that some people make to either steadfastly maintain their Métis identity against opposition, or to conceal it (if they can). Why choose one over the other? How does such a choice impact lives? I am fascinated by this. Why do some choose to be part of the culture, and some hide from it?

My writing also explores all the challenges that come with identifying as Métis later in life – the responsibility to the community and culture, the guilt of not having been raised in it. How Métis can someone be if raised White?

But I am also gripped by the joys of this new connection (to the past and the present), and by the strengths of knowing more about who I am and where I come from.

I fit into the world through my writing, and I now use writing to fit into the world as Métis.”

-

Treffrey Deerfoot is the Artistic Director of Blackfoot Medicine Speaks Dance Company and well known beadworker from the Siksika Nation and Blood Tribe of the Blackfoot Nation, Alberta.

“In Alberta and Saskatchewan, I am a well-known pow wow dancer, speaker and ceremonialist. I am a member of the sacred Horn Society of the Blackfoot people and a partner to a sacred "Beaver Bundle". I am strongly committed to preserving and transferring our way of life for and to younger generations.

Since the age of 4 I have been a dancer. At a young age I learned to bead from my grandmother whom was my primary caregiver. I have beaded and designed many numerous Blackfoot specific outfits for myself, children and grandchildren. As a result, my beadwork and outfit making has been commissioned by many fellow dancers. Presently I have complete outfits at the Royal Alberta Museum, Glenbow Museum, Calgary Airport, and Blackfoot Crossing Heritage Park.

My beadwork and outfits are true Blackfoot designs. Today many talented younger generation beaders and crafts people, bead beautiful generic pan-indigenous designs without a true understanding of the stories, traditions and knowledge of origins. Unfortunately, designs are taken from the internet and incorporated into many outfits and beadwork. In comparison, my family designs are congruent with the designs found in daguerreotype photos of our people. While one individual cannot stem the loss of culture, it is my hope that my work will stand as testament to what true Blackfoot design is in the modern world.”

-

Jason Eaglespeaker is a graphic novelist of Blackfoot and Duwamish descent living in Calgary.

“Indigenous art has been a part of my life since birth. My grandfather, the late Glen Eaglespeaker, was a renowned multimedia artist that traveled the world with me as a young boy. Today, my works draw upon the timeless teachings he passed onto me. One aspect of Indigenous life I felt wasn’t represented in art are traditional values (respect, humility, truth, bravery, honesty, love and wisdom). Sincere traditional values are the basis of culture, so as a result, I have always concentrated on showcasing their strength.

My graphic novel approach gives me the freedom to address aspects of Indigenous life that do not get proper attention (poverty, cultural “sellouts”, addictions, racism, unemployment etc). The graphic novel medium is truly innovative and allows me to fully express my artistic concerns, in the most traditional way of my ancestors - storytelling.

I've witnessed, first-hand, the destruction and trauma that resulted from residential schools and the horrific government policies which existed for all Canadian Indigenous people, all the way up to the 1980s (some schools were still open in 90s). From my great-great-grandparents, right up to my aunts, uncles and parents, residential schools have impacted those well beyond just survivors. This too, is reflected in my works.

My preferred art methods are graphic novels and comics (digital and print), pastel, watercolor, social media, interactive web design and smartphone applications - with a dual goal of revealing Indigenous-based values and enhancing awareness of contemporary/ traditional Indigenous issues.”

-

Dorothy Grant is a Haida fashion designer living in Tsawwassen, BC.

“I am a fashion designer and traditional Haida artist. For over 30 years, my Haida identity has been my foundation as a contemporary fashion designer. In 1986, I became the first to merge Haida art and fashion

I believe my clothing embodies a philosophy that is best described in a Haida word: YAANGUDANG, which means having “self respect for one’s self and others”; this is the driving force behind my work. For me it is about empowerment, pride and feeling good about oneself.

I believe my ability to maintain a quality line of clothing for 30 years, and remain true to my artistic ability has been one of my best achievements. I believe I’ve also helped in influencing in a positive manner many younger emerging fashion designers of native ancestry throughout Canada, The United States and New Zealand.”

-

Cris Derksen is a musician from the North Tall Cree Reserve, Treaty 8, Northern Alberta.

“I think this is a compelling time for Canadians as the lens towards First Nations folks has begun a shift towards understanding the colonial impacts our collective history shares. By fusing the European classical idiom with Traditional Powwow music I have created a vessel for the classical music community and the Indigenous community to meet equally and build new relationships.”

-

Jaalen Edenshaw is a Haida carver from Haida Gwaii, B.C.

“As a Haida person, my life’s work is to learn from my elders and ancestors and carry forward our culture, language, and relationship to the land. My work as an artist is rooted in this understanding and intention. The pieces I design and create all play a role in this process of experiencing, learning and sharing. As I work, I draw on the lessons that have been left to us by our ancestors in order to tell the stories of our land and people. Many of our ancestral works now stored in museums, or still standing in the ancient village sites around Haida Gwaii, show their artists’ mastery in their carving and painting, a mastery that represents centuries of refinement from the experience of living connected to the land and the sea.

While mainstream art may be divided into ‘modern’ and ‘traditional,’ our Haida tradition is alive and continuous, transcending this division. The thread we carry forward in our arts, songs, dance and story is without end and continues to gives shape to our past, present and future. Inseparable from my practice as an artist, I hunt, fish, gather seaweed, cockles and scallops, and process all of it to feed my family throughout the year. Continuing these practices allows me to connect with the essence of the shapes and forms of Haida formline design: a fish’s eye, the joint of a deer's leg, or the stem of a blade of sea grass.

The rules of Haida art that I have spent my life learning, in mentorships with Guujaaw and Jim Hart, and in my own work, guide my explorations of flow in formline, ovoid, and U. Within the intricacies of these visual and tactile rules, I have learned to play with forms and have conversations with the pieces left to us by past artists.”

-

Phil Gray is a carver of Ts'msyen (Tsimshian) and Cree First Nations descent living in Vancouver.

“I started carving at the age of 15. Early on, I had a few teachers to guide me. But it wasn’t until I began to study the old pieces of my ancestors, paying close attention to the Ts’msyen style, that I came into my own. While I have been viewed by many colleagues as a contemporary artist in my field, I consider myself a traditional artist following the old Ts'msyen ways.

But because my art is an expression not only of my heritage but also of my experiences, I have referenced pop culture from my childhood in some of my pieces. In addition, I have traveled to many countries around the world, and I have found a great deal of inspiration from the artistic traditions I encountered.

However, I believe that inspiration and artistic talent can only take you so far without something else that drives you to stay passionate and evolve artistically. When I first started out, it was fear that drove me. I spent the majority of my time trying to improve, trying to overcome my fear of not knowing my place in the art world. Frustration followed. I was frustrated that my potential wasn't obvious to everyone and I felt that I wasn't as good as my artistic contemporaries.

These days it's humility. I realize that creating art is not a race, that there will always be something else to learn, and that I can also teach others. Humility has rekindled my artistic passion as of late, and I've become driven to focus more on giving back to my people, sharing and passing on the knowledge that has been gifted to me over the years. Above all, I want to be remembered as a dedicated Ts'msyen artist.”

-

Ruth Cuthand is a visual artists and bead worker, Plains Cree, from Little Pine First Nation, Saskatchewan.

“Beads and viruses go hand-in-hand; new diseases and goods that traders brought to the Americas. I am alarmed by the contaminated water issues that are faced by many First Nation communities across Canada. I have beaded magnified bacterium and parasites that are found in the 94 First Nations that currently have boil water advisories. I have put these into resin inside glasses of all sizes.”

-

Todd DeVries is a Haida weaver from Skidegate.

“In 1999, I had a vision of the grandmother of the forest. At first I wasn’t sure who or what she represented, but after taking a hike through a cedar tree forest, I realized that the trees themselves are the grandmothers and learned a song/prayer to thank the spirit of the cedar, long life maker.”

-

Deantha Edmunds-Ramsay is an Inuk singer from Nunatsiavut, Labrador.

“There is a fascinating history in Nunatsiavut that goes back in time to the Moravian missionaries who travelled to Labrador from Europe centuries ago. They brought violins, cellos, trumpets, horns, and more. They also brought manuscripts of the music of famous German composers such as Handel and Haydn, as well as lesser-known composers of the Moravian faith. The Labrador Inuit learned to play various instruments of the orchestra, translated the lyrics into Inuktitut, and sang some of this beautiful music in 4-part harmonies at church each week. The Inuit made it their own.”

-

This bio was updated in 2024.

Theo Jean Cuthand is a filmmaker of Plains Cree and Scots descent and a member of Little Pine First Nation. He currently resides in Toronto, Canada.

Since 1995, Cuthand has been making short experimental narrative videos and films about sexuality, madness, Queer identity and love, and Indigeneity, which have screened in festivals internationally, including the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City, Mix Brasil Festival of Sexual Diversity in Sao Paolo, ImagineNATIVE in Toronto, Ann Arbour Film Festival, Images in Toronto, Berlinale in Berlin, New York Film Festival, Outfest, and Oberhausen International Short Film Festival. His work has also exhibited at galleries including the Remai in Saskatoon, The National Gallery in Ottawa, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, MoMA in New York, and The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. He completed his Bachelor of Fine Arts majoring in Film and Video at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in 2005, and his Masters of Arts in Media Production at Toronto Metropolitan University in 2015. He has made commissioned work for Urban Shaman and Videopool in Winnipeg, Cinema Politica in Montreal, VIMAF in Vancouver, and Bawaadan Collective in Canada. In 2020 he completed working on a 2D video game called A Bipolar Journey based on his experience learning and dealing with his bipolar disorder. Currently he is finishing his second video game Carmilla the Lonely, a lesbian vampire game about ethics. He has also written three feature screenplays and has performed at Live at The End Of The Century in Vancouver, Queer City Cinema’s Performatorium in Regina, and 7a*11d in Toronto. He is a Whitney Biennial 2019 artist. He is a trans man who uses he/him pronouns.

“I didn’t originally intend to be an experimental filmmaker. My work is largely dealing in a DIY aesthetic due to the very real experience of normally living in poverty. Experimental works are less costly for me to produce. If my actors are all pipe cleaner dolls, or if I am jumping around performing in a baby doll dress, or if I am delivering a lecture in front of a green screen with some footage of dandelions behind me, crucial messages can still be conveyed humorously and poignantly without the need for things like grants or patrons” (2017).

-

Cherie Dimaline is a Métis writer from Georgian Bay.

“I write literary fiction that speaks to a global audience from a very specific Canadian Indigenous perspective. My work delves into issues of identity, loss, ties and the severing of such, anxiety and the attempt to live with normalcy in an unnatural world. Through each story are the voices, stories, teachings and lands of my Anishnaabe and Métis grandmothers.”

-

Melissa General is a Mohawk/Oneida media artist from Six Nations of the Grand River Territory.

“My practice is heavily influenced by my Haudenosaunee identity, history, community and my relationship to the land. My artistic mission is to continually research and explore Indigenous history and culture, through photo, audio, video, language and performance; to further experiment ways of making in order to evolve my practice forward; promoting the knowledge and discussion of Haudenosaunee identity, culture and history.

I began primarily as photo-based artist with my practice expanding to include video and audio installation based works. My work is performative, exploring concepts of memory, history, land and Indigenous identity; discussing the notions of belonging and negotiating the intersection between urban life and ‘home’.

I maintain a strong relationship to my family and home community with the majority of my work produced on Six Nations Territory. My practice reflects my personal progress of understanding and recognizing my Indigenous identity through research, experience and exploration using my Indigenous body to address issues of identity, memory and land. I hope to continually expand this knowledge through my practice by further researching both my personal and community history and by developing my knowledge of Indigenous language to further discuss history, identity and culture from a Haudenosaunee perspective.”

-

Louise Halfe is a Cree poet from Saddle Lake, Alberta.

“I am a Cree poet, writer and author of four books of poetry and have been published in various anthologies. The books are as follows: Bear Bones and Feathers, speaks to the residential school impact on the community as well as of personal nature. The book also addresses the teachings of the old people and what still needs to be preserved. There are also letters of retaliation to the Vatican. Blue Marrow is a book of imagined relations with the newcomers as told through the various voices of imagined aboriginal women of the fur trade era. The Crooked Good is a narrative poem of the sacred legend of the Rolling Head. It is told through the voice of the mother who weaves the story from a Cree feminist perspective. Burning In This Midnight Dream was written after the Truth and Reconciliation events took shape throughout the country. The book is written from the personal thereby more intimate and immediate. It addresses lateral and horizontal violence though none of this sterilized jargon is utilized rather they are stories that have shaped history and the personal lives of residential school survivors.

I write these stories in hopes that it will help others to articulate the violence that has been perpetrated in their lives; shame, guilt and anger are braided and have a powerful hold on a person. It is my hope in sharing these stories in a poetic voice that more people will step up and demand from the government the resources that are needed to educate and help our communities heal. These poetic stories also record some of the untold history of the ancestors; these stories are fast disappearing as our Elders are fewer in numbers. The Canadian public as well need to be educated about the policies that we all inherited; these have silenced and crippled our communities. We all have a responsibility not only to share the history but to do something about it. This is my way of contributing to hope and to awareness.”

-

Tasha Hubbard is a filmmaker from Peepeekisis Cree Nation living in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

“My film and media work comes from my own desire to reconnect to my Cree family and history, as I was part of the 60s and 70s Scoop. My films reflect issues that I grapple with or that fascinate me and all are inspired by my Indigenous community. I did Two Worlds Colliding because the Starlight tours happened in my city and directly affected people I knew. I made 7 Minutes, a short independent film about a young woman who is part of the ‘almost missing’ because a man followed her home from the library and tried to put her in his van. These are issues that directly affect Indigenous peoples in Canada. But I also make work that reflects my interest in regeneration and resurgence of Indigenous culture. This is where my buffalo work is especially relevant. My independent film Buffalo Calling is about one particular herd’s survival in the face of near-extinction and diaspora. My next buffalo film focuses on Indigenous peoples’ contemporary efforts to repair our bond with the buffalo, one that was damaged after colonization. I am currently working on a feature documentary that looks at four 60s Scoop siblings recovering a sense of family that was denied to them. I am also writing an independent drama about a Cree family who decides to hide their children during the residential school era.

I like to push myself to make different types of films: investigative, experimental, dramatic, observational, and finally, with the new buffalo project, personal point of view. I took a hiatus from filmmaking to pursue a graduate degree but I am now once again immersed in making films.”

-

David Hannan is a Metis artist from Ottawa/Mettawa living in Toronto.

“My work attempts to challenge these representations while exploring a more complex understanding of Indigenous relationships to the land - relationships that do not fall within existing dichotomies such as ‘wilderness’ and ‘civilization.’

I call my sculptures ‘taxidermy hybrids,’ because their basic shapes are derived from taxidermy forms that I first manipulate in a variety of ways and then cast. Taxidermy forms have a unique character because they provide basic animal forms, but lack surface details that would be provided by animal pelts, such as fur-texture, ears, and so forth. As such, their simultaneous familiarity to and difference from the animals they represent give them an uncanny effect. This effect, combined with my own sculptural interventions create sculptures that shift between representation, abstraction and the hybrid blending of animal forms as a means of exploring issues of transformation and the vulnerability of humans, other creatures and the natural environment.

My work begins intuitively, often developing out of previous projects or my engagement with objects I find or otherwise encounter in the studio or out in the world. From there I work with the associations derived from these sources, often combining things in unexpected ways until they begin to generate meaning and aesthetic impact that seems worthy of being defined as a finished work of art.”

-

Jason Henry Hunt is a Kwaguilth carver working in Port Hardy, B.C.

“My name is Jason Henry Hunt from the village of Tsakis on the northern tip of Vancouver Island, BC. I come from a long line of carvers, in fact I apprenticed under my father Stanley Clifford Hunt who apprenticed under his father Henry Hunt. When I first started to carve I tried to distance myself from my family name as I felt it would be very difficult to make a name for myself being in the shadow of so many great artists. Twenty five years later I've been steadily carving and painting and building my own name to the point that I now actually use my middle name when I sign my work. I only recently started doing it as a sign of respect for my grandfather and to make sure people never forget who he was and the legacy he left with our family. I see myself as constantly striving to keep the standards he and my father set for me while taking the art form in my own direction at times as well.

I see now as I'm older and have been an artist for so many years that I've been lucky at times to be able to do what I love. The life of a carver is extremely rewarding but not an easy one by any means. It is an honour to share and carry on my family’s artistic tradition.”

-

Ya'Ya Heit is a carver from the Kispiox Band, Gitxsan Nation, B.C.

“As a long time professional artist, I am always interested in making public art. When I was younger, I only thought of having my family and neighbors see my works. Then I moved off the Kispiox Reservation and wanted the province to see my art works. In 1985 I moved to Ottawa, I thought the whole country could be my audience. Then the Olympics came to Vancouver, I wanted the world to see what I can create. NOW all I want to do is show the world NATIVE PRIDE: CANADIAN NATIVE PRIDE.

My ancestors and our lands have been foremost in my mind for most of my life. Some years I hunt and fish more than I carve. And so treaty making and politics are big in my life. I worked for my Gitxsan Chiefs for most of my life. Listening to and helping my Chiefs and elders, hunting and fishing for my Kispiox people, standing up for the tribe in court and on the land, road blocking. All that is fun to me, makes me proud to be Native.

All my histories and all my life comes out in my art works. The humor of events in my life, tragedies, accomplishments, lessons learned. Some years ago I noticed that I have created a lot of self portraits. This is my way of not breaking my Gitxsan laws of ownership of crests, who could claim to own a picture of me. And I have always enjoyed depicting my Gitxsan tribe’s cultural hero/teacher WiiGyet (BigMan, Raven). For my young children I started to write my own stories of HisOwn true modern day myths. Art of all kinds is important for all civilizations, not just my Gitxsan or Canadian civilizations.”

-

Shawn Hunt is a Heiltsuk artist working in Sechelt, B.C.

“My name is Shawn Hunt and I am an artist of both Heiltsuk First Nations and European Canadian decent. As a person of mixed heritage, I have always been interested in the space where these two cultures come together, the space that I occupy. I have trained as a carver, a jeweler and as a painter. I have learned traditional design from my father, but I also have a degree in Fine Arts. I have also studied as an apprentice with Coast Salish artist Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun in painting. I don’t feel that my work fits neatly into one specific category. It is not exclusively conceptual, traditional, contemporary, cultural or craft. Instead, I feel as though my work has elements of all of these categories. It is both ancient and modern at the same time. I am constantly seeking to push the boundaries of the Heiltsuk art form. My goal has always been to open up dialogue and create new discussions challenging the viewers perceptions about native art and native people. I deal with political, anthropological, or art historical subject matter. In subverting or remixing these categories I hope to incite a response. I like the idea of art being like a catalyst, or a flash point. I think art is most powerful when it poses questions, not when it gives the viewer the answers. My goal is to make the viewer think.”

-

Margaret Grenier is a Gitxsan/Cree dancer living in West Vancouver, B.C.

“I treasure dance as the most significant inheritance I have from my ancestors and the creative process is invaluable. I have dedicated myself to this large undertaking for the benefit of my children and to honour my indigenous heritage. I feel fortunate to be able to establish our artistic practices within the greater community and affirm our ability to regain our ancestral legacy in all its intricacy and eminence.

For me, dance has provided a protective environment to address the limitations placed on our Indigenous peoples and to create a healing space. Our bodies, our thoughts, our emotional attachments and our prayers are connected through the ceremony of dance. We are not only turning to our ancestral knowledge for our own reconciliation but we are sharing and supporting others through our art.

The artistic work of the previous era in my family’s lineage was in response to the lifting of the Potlatch ban and what was referred to as the slow awakening of a culture that was made to sleep for almost 70 years. Current social context has led to a critical stage in this long narrative of artistic practice. We find that we must evolve to meet the challenges of preserving the integrity and essence of ancient practices while responding to contemporary circumstances. The present creative processes will make certain that this essential progression will engage and respond resolutely with the responsibility of carrying forward what has been established by our predecessors, while defining the current legacy to be upheld.”

-

Tomson Highway is Cree playwright, novelist and musician from Barren Lands First Nation, Brochet, Manitoba.

“As I now speak 2 European languages fluently (and another 3 un-fluently), I aim to prove that, where European languages have room for 2 genders only, Native languages have room for many. This, I submit, is the source of the violence against women, and Aboriginal women most especially, by men, and heterosexual men only - the 2-gender system does NOT work; one gender has way too much power over the other; we need to explore other models. And the key just might be contained in the very architecture of Aboriginal languages, an ‘architecture’ where there is no gender, one where we are all, to one degree or another depending on who we are, both male and female. And one where God is neither male nor female. Or is both.”

www.tomsonhighway.comway.com/

-

Mark Igloliorte is an Inuit artist from Nunatsiavut, Labrador. He works in Vancouver, B.C.

Igloliorte works in a variety of practices with a focus on representational painting and drawing. He has created different series of works like observational work from his studio or specific periods of Inuit history such as the colonial transition of photos of kayaks along side European boats. Most recently, as a Inuk artist, his work seeks to connect Inuit culture to non-indigenous ones while underscoring the unique Inuit experience.

Komatik is a public art performance where a series of portraits are created of participant's dogs tied to the Inuit sled. While this performance is whimsical, combining domestic pets such as pomeranians with the komatik, during the sitting for the drawing the dog owners and Igloliorte discuss such matters as the role of the komatik in precolonial time, recent studies of how RCMP were ordered to slay sled dogs when Inuit populations were settled into communities, how Inuit ingenuity has been adapted the sled to work for snowmobiles and the dramatic effects of climate change for Inuit land during the winter.

Participants walk away with a portrait of their dog in front of a komatik along with a different understanding of Inuit culture. This performance was first delivered at the 'Art in the Open' festival 2014 Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island and is scheduled to be delivered again October 2016 at 'iNuit Blanche', St. John's, Newfoundland.

Recently, Igloliorte has began a new drawing project investigating the kayak as an Inuit form which has virally spread through out the recreational world.

http://markigloliorte.net/

-

Shannon Gustafson is an Ojibwe fine craft artist from Fort William First Nation, Ontario.

“I am an Ojibwe artist specializing in the area of custom beadwork and regalia making. I have been actively creating for 27 years. I consider myself to be a self-taught multi disciplinary artist. Powwow and it's culture is my main inspiration that has fuelled my artistic career. Among all things, beadwork is my passion. I enjoy experimenting with different types of beads, colors, and patterns. I have experience with both geometric and floral beadworking but being of Ojibwe decent, floral is what defines me. I enjoy incorporating natural components that were used historically, such as: shells, horse hair, porupine hair, quills, brass studs, bones, and birchbark. My work is well known for its quailty and use of color. My skills have definitely evolved over the last 2 decades and have since made a shift toward the older style of Ojibwe beadwork and patterns. My work may not be displayed in museums and galleries, but it does go on display every weekend from New Brunswick all the way to California and everywhere in between. I don’t have a degreee in fine arts, nor have I taken any formal arts training. My skills and artisitc abilities are those that cannot be learned in a classroom. It is the result of a lifetime of dedication, practise and a commitment to preservation. It is artwork that is admired by all people but most valued by my people. I will continue to challenge my abilities, nurture my gifts and preserve our culture through the arts.”

-

Jack Horne is a playwright of the Tsawout Band, WSANEC, Coast Salish, B.C.

“When I think of my teachings I think of my Mom because she is the one who gave them to me. When I wrote my first play, Indigenous Like Me, it was for her. The final scene of the play reads:

‘Now, no matter what I do I hear her voice. Doesn’t matter if I am studying the Indian Act at University or the history of colonialism, residential schools, or even feminism because it’s her voice I hear. It’s her teachings I remember and her life I think of when I approach those issues. And it makes me happy. It makes me happy because I realize that makes me Indigenous Like Her.’”

-

Geronimo Inutiq is a multi-media artist working in Montreal, Quebec.